Women have been wielding knives since the dawn of time. Prehistoric hunter, ancient priestess, medieval warrior, pirate, revolutionary or scientist: each one slices, cuts, explores, defends. Others fall under the blade. Secespita, dagger… the fixed knife reigned until the 15th century, when the folding knife appeared in pockets. But behind each blade lies much more than a simple tool. Knives accompanied women in their everyday gestures as well as in their exceptional deeds. It heals, nourishes, kills or liberates. The knife reflects a social condition, an era, a struggle. From vestals to samurai, Celtic queens to star-spangled chieftains, this article pays tribute to the women and knives that have spanned the centuries. And the story is just beginning.

Women and knives before the year 1000

In prehistoric times, women made primitive tools and took part in hunting and fishing on an equal footing with men. Madame homo abilis used flint, bone and obsidian to crush, cut, scrape and drill.

Sacrificial daggers of ancient priestesses

The sacrificial dagger of the Egyptian priestess Hetpet symbolizes the link between the world of the living and that of the dead.

For their part, the Vestals, purifying virgins, possessed a special knife: the secespita or secespite. This dagger cuts open the bodies of victims, often slaughtered with an axe.

🗡️ Some famous vestals: Rhea Silvia (the mythological mother of Romulus and Remus), Pompilia, Pinaria.

Agrippina murdered by dagger in ancient Rome

In 59 AD, Emperor Nero could no longer stand his overbearing mother. His advisors suggest that he disappear by shipwreck. But Agrippina, a good swimmer, takes refuge in her villa. Anicetus, Herculeius and Obitarius took it upon themselves to assassinate her. According to the historian Tacitus, the first blow of a stick hit her on the head. Then, when she saw the glint of the dagger’s blade, she pleaded “strike at the belly”.

Boudicca leads the Bretons against the Romans

A 1st-century Celtic warrior queen, Boudicca (or Boadicée) led the Bretons in a major revolt against the Roman occupier, C. Suetonius Paullinus. Her army used daggers, swords and axes.

Boudicca embodies the spirit of independence, courage and strength. Backed by the power of the Druids, she leads thousands of men and women into battle.

The Middle Ages: knives in the hands of women warriors

In the West

In the Middle Ages, noble ladies used the dagger. In addition to protection, the dagger also testified to the status, power, wealth and influence of its owner.

In the 15th century, Christine de Pizan wrote that “ladies must have the heart of men…, know the rights of arms… to assail or to defend”.

Historian Sylvie Steinberg explains that the education of young girls included taking the place of their brother. However, this prerogative for noblewomen stopped short of physical participation in combat.

Jeanne Hachette, the Beauvaisienne

On June 27, 1472, when the Burgundian herald summoned the inhabitants of Beauvais to surrender, they refused to parley. Faced with the duke’s weapons, they grabbed their bows, crossbows, couleuvrines and knives.

Jeanne Laisné pushes Charles le Téméraire’s Burgundians back with her hatchet. Her gesture motivates Beauvais residents to follow her to the ramparts to defend their “good city”.

In gratitude, King Louis XI exempted her from taxes for life.

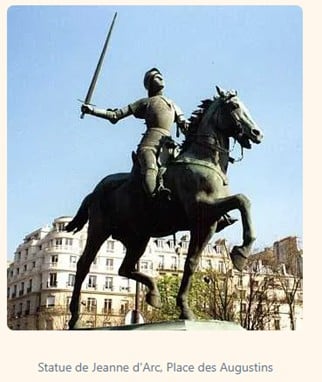

Joan of Arc, the Maid of Orleans

The young “ignorant peasant” symbolizes resistance during the siege of Orléans. Charles VII, the little king of Bourges, reigned over the Pays d’Oc, but struggled to combat the power of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, an English ally.

The archangel Saint-Michel appears to Jeanne in the guise of a knight accompanied by two saints. He urged her to lead the Dauphin to Reims and “drive the English out of France”. She met him in Chinon, where he had a suit of armor made for her. Her blade is said to have come from the chapel of Sainte-Catherine-de-Fierbois. It is said that, behind the altar, she found Charles Martel’s sword. The city of Orléans was saved on May 8, 1429. In Jeanne’s eyes, this victory proved the divine nature of her mission.

Asian women and knives

While in Europe women fought to protect cities and crowns, in Asia too, some took up arms.

In the 12th century, under the first shogun Yoritomo Minamoto, samurai women served as police officers. They supplied soldiers and defended feudal estates themselves.

The first female samurai warrior, Tomoe Gozen, killed Uchida Leyoshi at the battle of Awazu in 1184. Together with Hangaku Gozen and Takeko Nakano, she forms the legendary Japanese trio. Their favorite knife is a naginata, a pole topped with a blade. Takeko creates Joshitai: the women’s army.

🗡️ In 1555, Wa Shi leads her Chinese troops into battle on behalf of the Ming dynasty. She carries a Dao sword.

🗡️ In 1705, Mai Bhago led Sikh soldiers against the Mughals with a long, curved-blade knife.

Mary Read and Anne Bonny: the lady pirates

The two most famous women of female piracy dress as privateers, carry swords and wield daggers and pistols. Captain Jonathan Barnett captured them when he boarded John Rackham’s ship. Sentenced to be hanged, they “implored the belly” (claiming to be pregnant to escape death) and were granted a reprieve. Mary Read died in prison in 1721.

🔪 Knife models born in the Middle Ages: slicing knives, the parepain, the petit coustel, the wood trimmer, the oyster knife, the chopping knife, the rocking cleaver, the canivet.

🔪 In the 15th century, the folding knife appeared with pocket clothing.

The Renaissance: women fade but resist

The Renaissance and the influence of Catherine de Médicis kept women away from weapons. But some, like Kit Cavanagh and Hannah Snell, defied the law. Geneviève Premoy enlisted in 1676, disguised as a man, under the name of Chevalier Balthazar. When she was wounded, Louis XIV made her a member of the Order of Saint-Louis, but asked her to wear a skirt. It is said that she obeyed, but dressed in masculine tops (no, but!).

Only fencing shows show women with war swords, side or long swords, breastplates and helmets.

Alberte-Barbe d’Ernecourt Saint-Baslemont nevertheless defended her lands in the early 17th century, thanks to the military science passed on by her father.

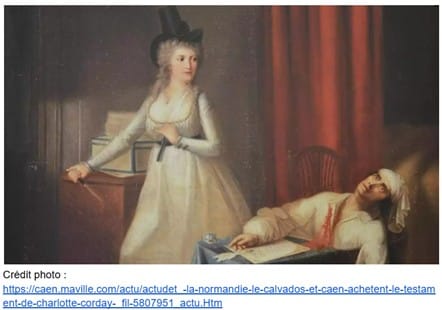

Revolution through Charlotte Corday’s blade

From an early age, Charlotte Corday admired Corneille’s heroes, such as Alcide. When Louis XVI died, she wept to see that “those who were supposed to give freedom were only executioners”. On July 13, 1793, she stopped at a cutler’s and bought a kitchen knife. The day before, in her Adresse aux Français amis des lois et de la paix, she referred to Marat as the “vilest of villains… falling under the avenging iron”.

In Rue des Cordeliers, she entered the home of the Deputy of the Convention and, with a firm hand, plunged the knife into his chest. She died four days later under the blade of the guillotine.

During the Revolution, women called on legislators to rule on their right to bear arms. Pauline Léon, in particular, wrote a letter that 300 other women signed. Théroigne de Méricourt spoke out in favor of arming women to “defend themselves against irons and defend the fatherland”. Men were reluctant to allow them to carry knives, a symbol of masculine virility.

The industrial era: women emancipate themselves and rediscover the knife

Marie Curie and her laboratory knife

On Rue Lhomond, in the 5th arrondissement, Marie Curie slices through a bag of black ore with the blade of her small knife. These 100 kilos of pitchblende from the only uranium deposit at the time marked a turning point in science.

After studying physics and mathematics, Marie Curie demonstrated that the radiation produced by uranium was an atomic property, not a chemical one.

With her husband, she also discovered polonium and radium, even more radioactive than uranium. The first woman professor at the Sorbonne, she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1911.

She left her mark on the 1st World War with her radiological ambulances: the “little curies”.

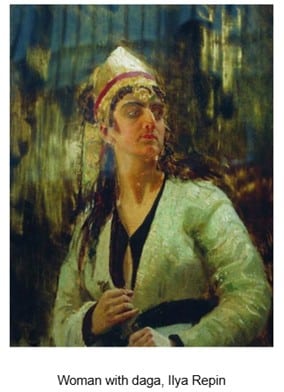

Woman with a dagger: the art of vulnerability and power

In 1899, Russian realist painter Ilya Yefimovich Repin saw the dagger as a symbol of women’s vulnerability and empowerment. The dagger represents the duality of life and death, defense and attack.

With this painting, Repin gives the so-called weaker sex a powerful, complex and emotionally charged voice.

In the 19th century, knives were used by many women’s guilds: cutlery makers, fish spinners, tannery workers, seamstresses, midwives (surgical blades), hairdressers and more.

20th-century women and blades

Eugénie Brazier, star chef

During the 1st World War, Eugénie Brazier made a name for herself with her famous poularde demi-deuil. In 1920, she opened La Mère Brazier, Lyon’s most famous restaurant. She won two stars in 1932, then three in 1933. In 1946, she introduced her chef’s knives and trained a young chef… Paul Bocuse.

Julia Child and her carbon steel kitchen knives

Born in 1912, Julia Child was a pioneer in the representation of French cuisine in the USA. Her first meal in France, featuring oysters, sole meunière and Pouilly fumé, was “an opening of the soul and spirit”. Author of the bestseller Mastering the art of French cooking, she talks to Time about her preference for knives with carbon steel blades. She finds them easier to sharpen than stainless steel knives.

The art of feminine cutlery

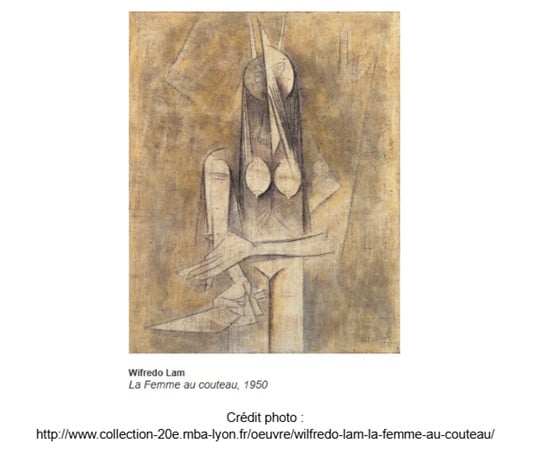

In 1950, Wifredo Lam’s painting La femme au couteau (an oil on canvas) presents the female figure with a large knife whose blade is turned towards the viewer. The work bears witness to Cuban, African and Oceanic art.

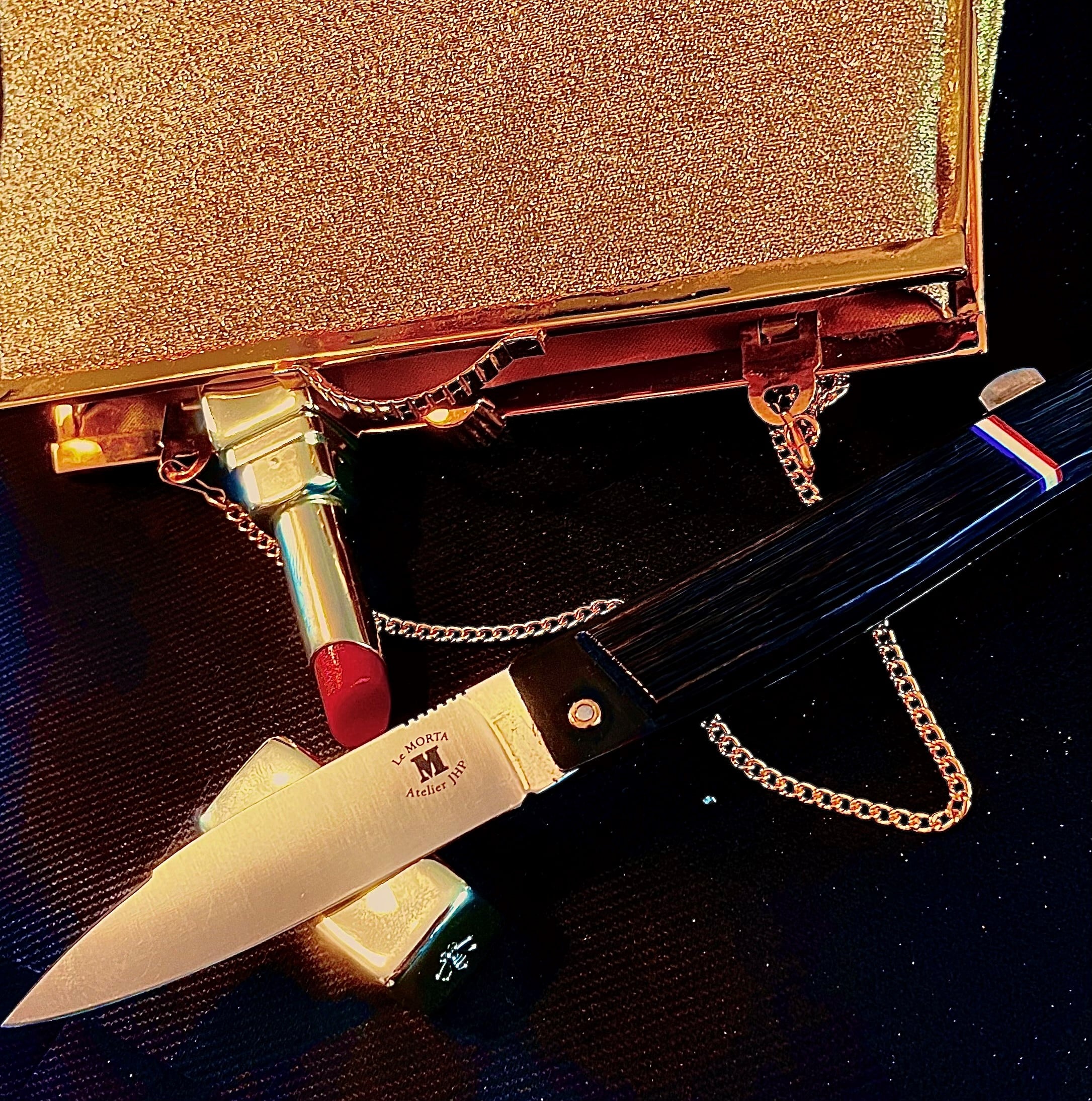

Today, women passionately perpetuate the craft of cutlery. They sculpt, forge, sharpen and engrave unique blades and handles, the fruit of know-how long passed down or patiently acquired. These creators of art, EDC and kitchen knives breathe new life into age-old traditions. They bring their sensitivity, their eye and their precision. In the workshop, Charlotte’s feminine hand combines finesse and technical mastery, with respect for noble materials. Morta wood, rare and thousands of years old, finds its rightful place in this craft of excellence, where each knife tells a story, that of the right gesture and living material.

Some fine female names in French cutlery: Danae Falcoz (art cutler), Ellia Jouveaux (specialized in engraving), Stéphanie Mara (cutlery designer), Elise Richard and Pascale Sabaté. Sonia Rykiel is a notable presence among the women and knives.

Knives have been part of women’s daily lives for centuries. In their hands or in front of them, blades have nurtured, defended or killed them. From carved flint to hand-engraved blades, knives take the form of objects of survival, power or creation. They tell a parallel, sometimes forgotten story. A cutting destiny, both intimate and universal. Today, women use fixed knives and pocket knives in the same way as men: in the kitchen, in the wilderness, for decoration, DIY or gardening.

Our sources

- The stories of Boudicca ; Jeanne Hachette ; Marie Curie ;

Article written by Christelle Lorant 🪶

Thanks to Mickael Texier for the cover photo.

The article’s key questions

What role have women played in the art of cutlery throughout history?

Since prehistoric times, women have wielded knives as an essential survival tool. Over the centuries, they have evolved from simple users to veritable artisans of the art of cutlery.

In the 19th century, they made their mark in many guilds as cutlery makers, fish spinners and tannery workers. Today, women designers passionately perpetuate this age-old tradition, bringing their sensitivity and precision to this craft of excellence.

Names like Danae Falcoz, Ellia Jouveaux and Stéphanie Mara illustrate this know-how, which combines finesse and technical mastery, while respecting noble materials, as we do at Couteaux Morta with morta wood. The status of women in this field has evolved considerably, transforming what was once a male profession into an artistic practice accessible to all talents, regardless of gender.

How has the evolution of blades accompanied women's emancipation?

The relationship between knives and women has followed the emancipation of the latter. Initially simple survival tools in prehistoric times, knives over time became symbols of status and power for women. The major revolution came in the 15th century with the appearance of the folding knife, which was born with pocket clothing, making the tool more accessible and discreet.

In the 20th century, figures such as Eugénie Brazier, the first three-starred chef, and Julia Child, who preferred carbon steel blades, illustrated this emancipation through the mastery of professional tools.

This growing diversity of knives has helped transform the place of women in fields such as gastronomy, where they have been able to demonstrate their excellence and take their place in territories previously dominated by men.

What is the symbolism of the sharp knife in the history of women warriors?

The sharpness of the blade has symbolized the duality between vulnerability and feminine power. Figures from Boudicca, the 1st-century Celtic queen, to Charlotte Corday during the French Revolution, have used the knife as an instrument of resistance and combat.

For medieval noblewomen, the dagger was both a protective accessory and a symbol of wealth and influence. Female samurai like Tomoe Gozen wielded the naginata with formidable efficiency. Even when the Renaissance tended to keep women away from weapons, some, like Alberte-Barbe d’Ernecourt, defied these restrictions.

Ilya Yefimovich Repin’s “Woman with a Dagger” (1899) illustrates this ambivalence, where the blade becomes a symbol of emancipation. This long history shows how the knife has enabled women to take their destiny into their own hands, transforming a simple object into a vector of power and feminine identity through the ages.

How have innovations in contemporary cutlery redefined feminine practices?

Today, a wide variety of models can be used to meet specific needs. Modern materials such as high-performance steels have enhanced blade quality without compromising sharpness.

The town of Thiers, with its Cutlery Museum, remains an important French historical center for this craft. Design has become a central element, transforming the knife into a veritable work of art for everyday use. Cases and accessories have also diversified, making these tools more attractive.

Whether for professional or domestic use, this evolution has helped to normalize the use of knives among women, redefining their relationship with this ancestral object in this field of excellence.

What contribution have gold and precious materials made to the art of women's cutlery?

Throughout history, daggers and daggers have been status symbols. In the Middle Ages, noble ladies used the dagger as a symbol of status, power, wealth and influence. These exceptional pieces illustrate the refinement typical of certain historical periods.

Contemporary craftsmen like Danae Falcoz perpetuate this tradition of excellence. The Musée de la Coutellerie is a reference to this heritage. Today, women use knives in the same way as men, whether for cooking, DIY or other daily activities.

This evolution shows how the knife has gone from a gendered symbol to a universal tool, transforming its perception across generations and social practices.

How have women artisans transformed new trends in cutlery?

Women artisans have brought an innovative vision to cutlery, enriching this traditionally masculine sector. Thanks to their sensitivity, they have created unique models that combine finesse and technical mastery, while respecting noble materials.

Designers such as Elise Richard and Pascale Sabaté use their talents to create exceptional pieces. Through their work, these craftswomen contribute to keeping alive an age-old tradition while adding their own personal touch, perhaps illustrating a new era in the history of cutlery in which women are playing an increasingly important role.